At the suggestion of a doctoral student I met at a robotics conference, I did a series of interviews with some of my elementary robotics students. I started a program this year that consists of robotics projects at every grade level from preschool to grade 6. Additionally, there are open ended engineering challenges, based on robotics, at grades K, 2, 4, and 6. These consist of challenges like building your own burglar alarm or carnival ride instead of the standard projects where they build a design from the book.

The kids repeatedly said that the projects were fun (this was mentioned some 24 times with the next most common being that they liked that it was hands-on, which was mentioned 13 times. When I asked them why it was fun, they said because it was hands on or that that it was satisfying at the end or that it was different. I say the same things in my and grant applications: hands on is better, fun, a good way to learn, etc.

But I was left feeling that I was not getting at the core idea of why it was fun for them.

At the same time, I was editing some videos of my son Aidan. I try and create a DVD made up of movie clips and a slideshow every 6 months. Aidan, my wife Dawn, and I love to watch them periodically. I am fascinated to both see how Aidan has changed and how he stayed the same.

Here’s a clip of my son Aidan playing with some Lego blocks. I have always loved this creative, dramatic play that he does with blocks. He also does this type of play in the bath.

I have been thinking that I will miss this when it stops and was assuming it was just something all kids do and all kids grow out of.

But I was out running one day with my dogs and it hit me, that the fun the older kids are having with robotics has a connection to the creative play my son and presumably all kids do.

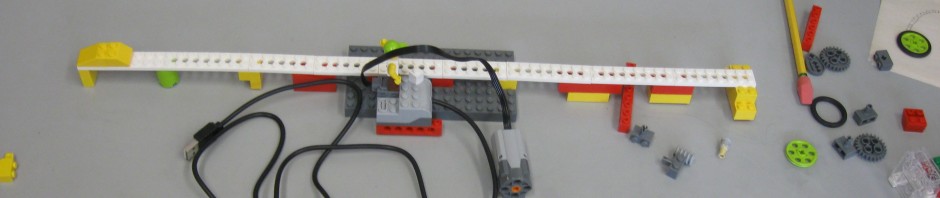

In kid’s creative play, they create – with blocks or other toys – their own microworlds that they have absolute control over. The building seem to be in service to or a prelude to the dramatic, creative play that follows. This dramatic play has characters, plots, and many, many sound effects! As I watch children PK-6 work with robots, I see aspects of this creative play, especially in open ended challenges where they can build their own design. I see some of that fade, at least explicitly, over time. However, I did see, even in this year’s sixth grade class, some Lego characters attached to cars in different ways.

Then, when out a run one day, it hit me that robotics taps into the creative play younger kids do. Robotics is creative play for older kids.

How much do we tap into this at school? Not very much! Students were clear that one of the reasons that robotics was so fun was that it was different, not something they usually do, and where they get to build, and get to do things without teacher help or following directions. Aren’t those reasons some of the key features of creative play?

I think we tap into some of the creative play instinct in creative writing and art, which tend to be more attractive to girls, speaking very generally. But very few teachers tap into the (typically boy) activities of blocks and/or Legos. I always had a take apart center in my third grade classroom, where students could take apart electronics gear and old typewriters. This attracted many boys, especially those with learning disabilities (LD) and/or attention deficit disorder (ADD). We have seen the same thing with elementary robotics, where many boys with LD or ADD that do lots of Legos at home can really shine and be stars and helpers in their classrooms where they usually struggle.

I think we are missing many boys in elementary school by not tapping into this creative play instinct. Somehow, corporations are not missing this point however, by creating and selling billions of dollars of action figures and other toys that do tap into creative play, sometimes in ways that are not as constructive as they could be. We are not tapping into this at schools, if anything we are actively repressing it.

This Ted Talk by Ali Carr-Chellman does a great job of laying out some of the reasons elementary schools are failing boys.

A teacher I work with has always wondered why games we do such as My Make Believe Castle, SimTown, and SimCity are so popular with kids. Again, I believe these “god” games, where the player controls their own microworld, tap into the creative play instinct that is so strong in toddlers and preschoolers.

Even though this insight answered many questions for me (and is theory and not proven), many more emerged.

How does this creative play instinct evolve over time? Are there developmental milestones ala Piaget that are similar for creative play/building/engineering?

How does it fit into Multiple Intelligence Theory? MI Theory does not seem to have a corresponding intelligence for the creative play/building/engineering that I am talking about.

How does it fit into our aboriginal roots? Have children always built and played with things in some way? How has this evolved over time and what survival value did it have originally?

Why do preschoolers and toddlers, who do everything – music, dance, drama, humor, sports, art, language, building, social, nature, spirit – eventually stop doing everything? Are they forming their identity and self selecting things that correspond to their natural talents and interests? Are we culturally selecting certain aspects of personality, with only those with very strong inclinations, able to keep those going? What are the effects of schools valuing some of these over others?

Does the relative lack of engineering and building experiences in elementary schools narrow the pool of students have may had inclinations towards engineering? By the time they are exposed to engineering in high school (if at all), is it too late?